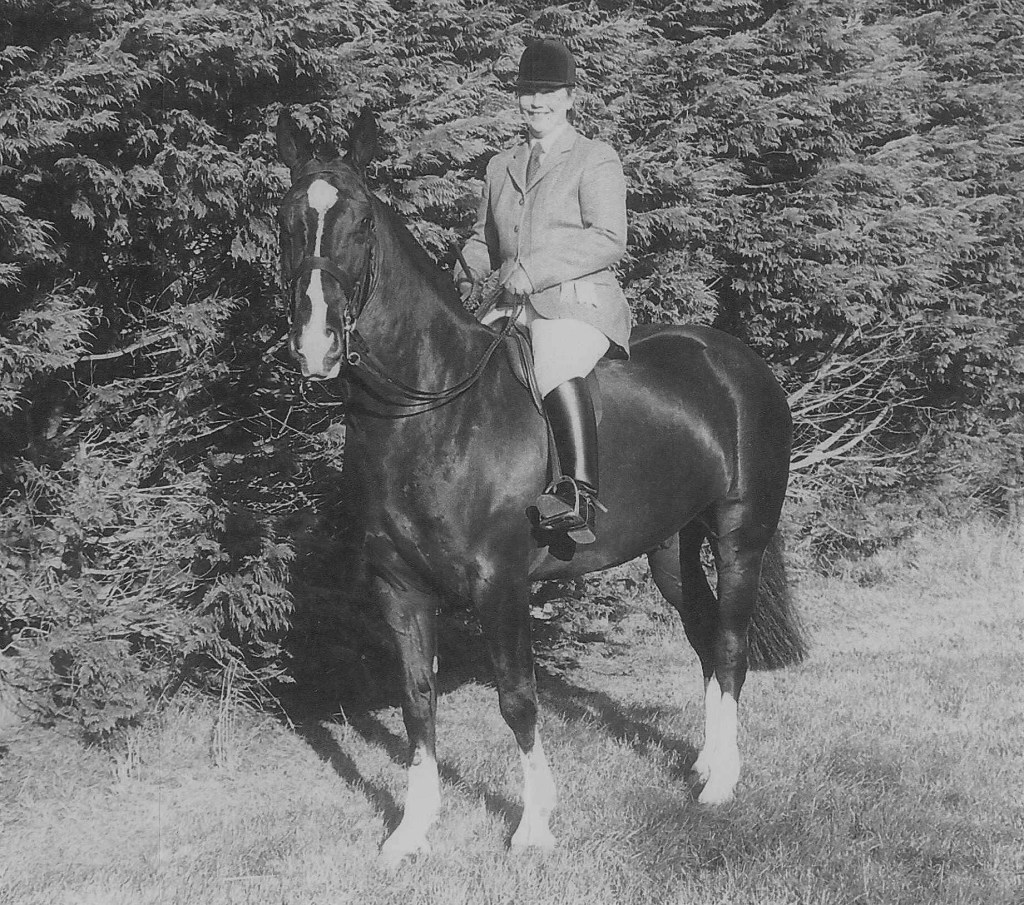

Through the records in his Irish Horse Passport, I traced Bruce’s early years in Ireland. A previous owner sent me this photo of him as a five-year old. With allowances for creative licence, I’ve dabbled with fiction and written his story:

Southern Ireland is famous for the craic, the Guinness and the rainfall but even by Irish standards, the spring of 1994 was unseasonably wet and cold. In a field where coastline meets countryside, and horizontal shards of rain drive straight from the sea, the foal was born on a moonless May night. He was a large foal and although his mother had produced many before him, this one came at great cost to her elderly body. She was too weak to lick her newborn let alone encourage him to suckle, and they lay together in the wet grass until daybreak, when the farmer found them on his early morning rounds.

Cussing that his inattention could cost him dearly, he hoisted the foal up onto his shoulders, and with the mare following, took them to a waiting barn where old straw was piled up high to make a warm bed. What the bed lacked in freshness it gained in depth. He twisted straw into a rope, and then into a pad and roughly massaged the mother and foal. As warmth returned to the mare’s body so did maternal instinct, and she began to wash her foal. The farmer sat back on his haunches in the straw to have a closer look at his ill-advised ‘investment’.

The standing foal wobbled and fell and wobbled again before finding his mother’s udder. He suckled noisily, his feather-duster of a tail bobbing up and down as he grabbed greedily for milk. As the farmer noted his handsome head with bright white star shining like a beacon, his soft pink muzzle surrounded by a web of spidery whiskers, huge shoulder sloping like an anvil, disproportionately large backend and four white socks, he mentally ran through the ancient adage “one white sock keep him all your life, two white socks give him to your wife, three white socks give him to your man, four white socks sell him if you can.” Well that was the plan; the mare’s value was in her foal fathered by a local Irish Draught stallion, and she had the graceful thoroughbred bloodlines to soften any plain traits passed down with the sire’s strength. Pleased with the look of this foal, the farmer almost allowed himself to pet the mare for her effort. He wasn’t a cruel man, just ignorant; he had bought the broodmare cheaply at the sales, wanting to make as much money as he could with as little effort as possible.

The mare and foal spent the rest of that summer alone in the boggy paddock. Without a helping human hand to provide extra food, the mother struggled to produce milk and neither of them thrived. The mother could barely look after herself let alone teach her foal valuable life lessons, and the foal hung back, absorbing her anxiety instead of pushing boundaries in what should have been a confidence-building new world full of wonder. He was always hungry.

As late autumn headed towards winter, the cold wind blew in from the coast and the old mare lost what little bodyweight remained. The farmer slipped a halter over her scraggy head, led her into the same barn (with the same bedding) and the foal followed at a cautious distance. Once the foal was inside the barn, the mare was quickly pulled away, the door boarded up and the foal left alone in the dark to scream and holler. The mare was led into the waiting lorry and taken to the hunt kennels. By lunchtime she was dead, leaving hounds complaining about their sparse rations. In her youth she’d won many races, and as she aged she’d bred many fine foals. She’d done her job and the circle of life was complete.

In the dark stable the foal begged for his mother, begged for comfort, begged for milk and vainly flapped his lips together . . . a habit that would last a lifetime.

After his traumatic weaning, the black colt retreated within himself, alone in the paddock for two long winters. When the farmer and a companion visited one morning, he registered little interest and continued grazing at a distance. Giving himself time to watch the farmer whom he dismissed with disdain, he noted that the companion trod with the ease of someone totally in charge, and spoke softly as if he had something interesting to say. The colt flicked one ear forward and momentarily stopped eating. He felt a primeval need for a safe leader surge through his body, rippling his thin coat and making him shiver with anticipation.

The man spoke to him so quietly, the colt had to move alongside to hear the tone, and he stood calmly as the quiet man ran the palm of his hand softly down his neck. It reminded him of how his mother had licked him, and he liked it. As he stood, he noticed the man’s coat smelt of nice things, and he liked that too. The dealer’s hands felt his legs, his rump and his ribcage, and the colt felt warm and secure.

Suddenly, the farmer waved his arms and shouted, and slapped the colt to make him run away. Bucking and kicking, he galloped to the far end of the field, wheeled round in a large arc and trotted back to the dealer man, who smiled and nodded, and breathed out slowly in answer to the colt’s anxious breath. A rapid exchange of words passed between the two men, concluding with a wad of notes being pressed into the farmer’s hand. The farmer brought the mare’s old halter from the barn, and before the colt knew what was happening, he was manhandled into a trailer and driven away from a life he never quite forgot.

After travelling for about an hour, the Landrover and trailer turned through metal gates and parked in a large well fenced field. The colt was loose inside the trailer, and the ramp was barely down before he fled its confines. The grass under his feet was long, lush and green. He put his head down and ate, great tufts of goodness torn nervously and devoured greedily. He continued eating as five field-mates cantered towards him, bucking leaping and running amok like a bunch of carefree hooligans. They squealed to a halt at the fenceline before wheeling round in unison, and trotted towards the shade of the trees. Four of the colts began to graze with apparent nonchalance but the fifth, a stocky bay who was large in stature if not in size, walked towards the black colt with the swagger of a born leader and barged straight into him.

The black colt’s teeth were momentarily separated from the grass. A challenge was annoying enough, but any interruption that stopped him eating was far more irksome. The two colts faced each other. The black colt had no confidence, no experience of other horses and no social skills but he had greed, and great strength comes with any kind of greed, so he promptly turned his back on the bay colt and let fly with both back legs powered by his disproportionately large backend. The bay reeled in indignation and pain as a flying hoof made contact with his shoulder, but came straight back to do battle. Refusing to be side-tracked, the black colt waved a back leg with threatening intent and flattened his ears flat against his head, and continued eating. The bay had no option but to rejoin his friends and no-one bothered the black colt again. He didn’t play, he didn’t enjoy mutual grooming, he didn’t help swish flies or gallop with the wind in his tail, didn’t bite and nip and test the pecking order or look for imaginary monsters. He just ate.

The black colt lived among but not ‘with’ the others for two more winters. They were all gelded together, returning to the field somewhat more subdued and the black felt most pain and took longest to recover. He remembered his mother and flapped his lips for comfort. All six boys had daily lessons learning how to walk in-hand, carry a saddle and wear a bridle. The girl grooms leant across their backs and they were long-reined with sacks tied to the saddle. The farrier trimmed their feet and they became accustomed to cars and tractors. The black horse was eager to please, very quick to learn and more compliant than his classmates and the girls loved him. He liked being petted and he liked to have someone in charge but most of all he liked to eat. He didn’t like being scolded or having his thin coat brushed with rough brushes and he didn’t like being shut in a stable.

Appraising his crop of youngsters in the summer of their fourth year, Ned Mahoney smiled with satisfaction at a job well done. They had grown fat and sleek. The young black cob was the pick of the bunch and looked outstanding with his arched neck, deep body, broad chest, strong loins and hugely powerful backside. His mother’s thoroughbred breeding showed in his clean featherless legs and elegant head, silky coat and well set tail, but most of her characteristics had channelled themselves into his temperament. With some trepidation, Ned recognised that this middleweight cob was more like a thoroughbred than many racehorses he’d known, and wondered what life would be like for one so sensitive. With the Irish showing season about to begin he moved the black horse, the bay, and a nicely marked piebald into a field alongside the road where he’d replaced the high hedge with a post and rail fence. Three fine youngsters for sale to suit all tastes, and he believed in giving prospective purchasers a roadside view.

In the early morning mist, Hilary Marson loaded her two show horses into the lorry, closed the ramp and hoisted herself into the cab. Another showing season, another batch of young horses for training and selling, and hopefully enough money earned to pay for a long-awaited roof repair on her house. Having done a days work before the sun came up, she contemplated the competition ahead and thought ruefully of her comfy bed and assorted dogs still sleeping there. Taking the top road out of the village she had just enough time to drive past Ned’s farm and see what was in the viewing field.

You had to be quick with Ned. His sales patter might always begin with the line “I’d have kept this ‘un if only I had the room . . .” but as a middleman able to see potential in a gangly youngster, he had the best horses for miles around, flourishing (he said) on fields fed by holy wells. Whatever his secret, many champions had come from his farm. Gently shifting the lorry’s gears in order not to jolt her precious cargo, Hilary reached the field and saw two horses snoozing side by side; a nice bay somewhat light of bone for her taste and a piebald with a ponyish head. She had her foot back on the gas ready to drive on when she noticed the black horse grazing slightly away from the others, head down tucking into a dewy breakfast. She turned the steering wheel and headed the lorry up the farm drive.

The deal was sealed within thirty minutes. As the black horse was loaded into Hilary’s lorry, he flapped his lips with anxiety but didn’t call out. The two horses already standing tied in the lorry flared their noses in greeting and remembered the morning they too had come from the same field. Hilary named the black cob Ned after the dealer, but with his flapping lips, he was registered in his passport as ‘Look Who’s Talking’.

Ned thrived with Hilary and her dedicated team. He overcame his fear of being stabled but at the first sign of anything stressful he would rasp the walls with his teeth creating great gashes across the wood panelling. He loved the grooming massages with soft brushes, and his silky coat shone beneath the groom’s powerful hands. He had a season’s hunting with Hilary’s head girl who found him excitable but controllable, and with his sensitive mouth there was no need for a strong bit to give extra brakes. He took to jumping like a duck to water, and as long as his jockey gave clear instructions he would face any obstacle with confidence, leaping hedges and rails, gates and ditches like an old-timer with athleticism that belied his stocky frame!

Hilary taught him balance and cadence and delighted in the lightness of foot his schoolwork brought. His barrel body became toned and honed, his neck increased its magnificent arch and his bottom developed a deep cleavage. Measuring 15.3hh he was perfectly proportioned for a maxi cob, echoing the judges from yesteryear who decreed a show cob should have “the face of a duchess and the backside of a cook.”

His manners were impeccable. He automatically stood square, galloped like a seasoned hunter and won every cob class he entered, charming judges and spectators alike by flapping his lips with perfect comic timing at the prize-giving. Throughout the year Hilary turned down many requests to buy Ned, but as he left the ring at Dublin Show decked in his winning ribbons, the deal offered by the Englishman could not be bettered. She put Ned’s saddle back in the lorry and watched with great sadness as he was led away. As she began her journey back to her quiet village, the black cob began his journey to his new life in England.

…even more now.

LikeLike

Anna, is that possible?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Now …. that was a good read!

LikeLike

I hope it made it in time for breakfast Kimberley 😉

LikeLike

What a start in life, Elaine he is just so handsome.

LikeLike

I have to agree with you on that Debbie, but them I am a tad biased!

LikeLike

Hi, Elaine. I loved reading this “story” of Bruce’s early life. Photo is great, is that him ? I think you could be a fiction writer, well, wait a minute, you already are, and here’s the story to prove it.!! . enjoyed reading it so much, while biting my nails about the young horse’s early dire situation in life.

This reminded me that a horse I had briefly in 2011 , Lightfoot, had the nickname “Smack” because of how he would smack his mouth when anxious. It was very noticeable, Happy to report that even though he died an untimely death at 12, that worried “tell” of his dissipated after I bought him. . The former owners/trainers would ride him and shoot wild hogs off his back ! No wonder he was worried.

Thank you for sharing this good story with us. It’s so convincing I am sure there is more than one grain of truth in it.

LikeLike

Sarah, yes that’s a picture of young Bruce. The lady writing him was a show judge.

It sounds like Lightfoot had the same smacking lip flap, I’m glad he lost his anxiety with you. Wild hogs are pretty scary things!

I do feel there’s some truth to the story, its strange what you learn from a horse.

LikeLike

Such a compelling story and written with such deep awareness of the subject. This displays yet another aspect of your writing that is very impressive. Well done, and please, may we have some more?

LikeLike

thanks Susan, yes I will try and write some more, I’ll have to get Bruce to suggest something

LikeLike

I want to know more about Bruce’s life after joining you in England. I am a sucker for a well-developed character and you hooked me with Bruce!

LikeLike

boy oh boy Amy, Bruce has character down to a fine art!

I will try to write more fiction, but you know what its like with the Cloud of Doom, when you use writing to process real life.

However, I’ve just started another course of steroids to try and shrink some inflammation, and sleepless nights are the new norm so I’ll have more writing time.

LikeLike

Oh wow, you got me with that. And me a short story dis-liker and non-horsey person – converted in one fell swoop.

LikeLike

thanks Sue that’s music to my ears! I’ve ben busy writing the next instalment, but the story might not be so short next time…

LikeLike